The Cross-Platform False Positive Problem: Why Vulnerability Scanners Flag Windows CVEs on Linux

Security teams keep tripping over the same absurd issue: vulnerability scanners reporting Windows-specific flaws on Linux systems, and vice versa. It clutters investigations, inflates dashboards, and makes every metric less reliable. The real challenge is unpacking how scanners arrive at these conclusions and what it takes to stop the noise at the source.

The Problem: Platform-Specific Vulnerabilities on the Wrong OS

Consider a Linux container running a Go-based application in production. Your vulnerability scanner flags CVE-2023-45283, a path traversal vulnerability in Go's filepath package with a CVSS score of 7.5. While CVSS scoring has significant limitations, we'll reference it here as it's what most scanners display. The description mentions Windows paths with \??\ prefixes and Root Local Device paths. Your team investigates, only to discover this is exclusively a Windows path-handling vulnerability that cannot be exploited on Linux systems. Despite your entire infrastructure running on Linux, the scanner flagged every Go binary because the Go compiler theoretically contains the vulnerable code path, even though that code never executes on Linux.

This scenario occurs across vulnerability management programs daily, creating several problems:

Operational Impact: Security teams waste hours investigating irrelevant findings, diverting resources from actual risks.

Metric Distortion: False positives inflate vulnerability counts, skew risk scores, and misrepresent actual security posture. Management dashboards show critical vulnerabilities that don't actually exist, leading to poor prioritization decisions.

Alert Fatigue: When scanners regularly report impossible vulnerabilities, teams become desensitized to findings.

Why This Happens: Understanding Scanner Detection Logic

1. Package Name Collision

Some software packages share identical or similar names across platforms but are entirely different codebases. A scanner detecting "package-name-1.2.3" may match it against vulnerability databases without validating the platform context.

Example: The Go programming language compiles to platform-specific binaries, but vulnerability databases often list Go versions (e.g., "golang 1.20.10") without platform qualifiers. CVE-2023-45283 affects Go's filepath package but only on Windows, yet scanners flag it on any system running that Go version, regardless of OS.

2. Software Metadata Confusion

Scanners often rely on CPE (Common Platform Enumeration) identifiers or package metadata. If this metadata is incomplete, ambiguous, or incorrectly parsed, scanners may match vulnerabilities to the wrong platform.

Example: A scanner detecting version "3.5.1" of a library might match any vulnerability for that version number across all platforms, ignoring the OS component of the CPE identifier.

3. Container Base Image Detection Failures

In containerized environments, scanners may detect artifacts from multi-stage builds or build-time dependencies that aren't present in the runtime container. More critically, scanners often can't distinguish between code compiled into a binary versus code that exists in source but isn't included in platform-specific builds.

Example: A Go application compiled for Linux includes the filepath package in its binary, but the Windows-specific path handling code isn't compiled into the Linux binary. Scanners detecting "golang 1.20.10" flag CVE-2023-45283 without verifying that the vulnerable Windows code path doesn't exist in the Linux-compiled binary.

4. Transitive Dependency Assumptions

Scanners sometimes flag vulnerabilities in the entire dependency tree without verifying whether dependencies are actually installed or loaded. A package.json or requirements.txt might reference Windows-specific packages that are never installed on Linux deployments.

How to Address Cross-Platform False Positives

While modern platforms like Maze provide built-in exploitability assessment, many organizations still work with traditional scanners. Here are practical approaches security teams implement to handle these false positives:

Platform-Based Filtering

Most vulnerability scanners support OS-aware suppression rules, though they require manual configuration and consistent rule updates. Security teams should create exclusion rules that automatically suppress vulnerabilities when there's a platform mismatch between the CVE requirement and the actual system OS. Depending on your scanner, this could be a significant amount of work, so have clear examples in mind when you begin.

Asset Inventory Validation

Other teams attempt to correlate scanner output with asset data from places like CMDBs, cloud provider APIs, or configuration management systems. Automated scripts can then cross-reference the detected OS against required platforms and flag mismatches for suppression.

Binary Verification

For language-specific vulnerabilities, teams should verify what's actually compiled into binaries. For CVE-2023-45283, checking the Go binary's target platform (GOOS=linux) provides definitive proof that Windows-specific code isn't present.

Documented Exception Management

Security teams maintain formal exception records with technical justification:

- CVE and affected assets

- Evidence of platform mismatch (OS verification, binary analysis)

- Risk assessment confirming non-exploitability

- Regular review schedule

This creates an audit trail for compliance while reducing repeated investigations.

Analyst Triage Procedures

Teams develop SOPs for quickly identifying platform mismatches: verify asset OS, check CVE platform requirements, validate with secondary sources, document, and suppress if a mismatch is confirmed. This reduces time spent on repetitive investigations.

Real-World Example: CVE-2023-45283

Let's examine CVE-2023-45283 as a concrete case study demonstrating how cross-platform false positives occur and why they're problematic.

The Vulnerability

CVE-2023-45283 is a path traversal vulnerability in Go's path/filepath package affecting versions before Go 1.20.11 and 1.21.4. The vulnerability specifically involves improper handling of Windows paths beginning with the \??\ prefix, a Root Local Device path equivalent to \\?\.

The vulnerable behavior: On Windows, the filepath.Clean() function could convert a rooted path like \a\..\??\b into the root local device path \??\b, potentially allowing directory traversal. Similarly, filepath.Join() could construct dangerous paths from seemingly innocent path components.

Critical detail: This vulnerability ONLY affects Windows systems because the vulnerable code path specifically handles Windows path syntax. Linux and Unix systems don't process \??\ prefixes; these paths are meaningless on non-Windows platforms.

The Scanner Problem

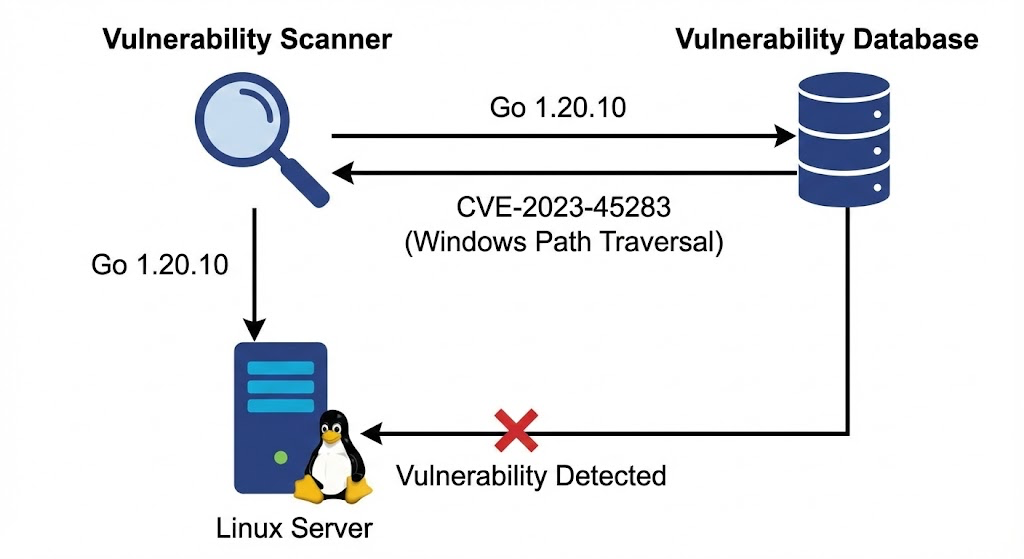

Despite being Windows-specific, CVE-2023-45283 was flagged by vulnerability scanners on Linux systems running Go applications. Why?

Scanner detection logic:

- Scanner detects Go binary (e.g., golang version 1.20.10)

- Scanner queries vulnerability database for golang 1.20.10

- Database returns CVE-2023-45283 as affecting golang < 1.20.11

- Scanner flags the vulnerability, regardless of the underlying OS

The scanner sees "Go version contains vulnerable code" and stops there. It doesn't evaluate whether the vulnerable code path can actually execute in the deployment environment.

The Broader Issue: Detection vs. Exploitability

The cross-platform false positive problem exemplifies a fundamental challenge in vulnerability management: the difference between detecting a vulnerability and determining exploitability.

Detection answers: "Is there something that matches a CVE pattern?"

Exploitability answers: "Can this CVE actually be exploited in this specific context?"

Many vulnerability scanners excel at detection but struggle with exploitability assessment. They apply pattern matching without sufficient context validation:

- They detect package names without verifying platform compatibility

- They flag vulnerabilities without checking if vulnerable code paths are reachable

- They report theoretical risks without considering deployment architecture

CVE-2023-45283 demonstrates the fundamental gap between vulnerability detection and exploitability assessment:

What scanners detect: "This Go binary was compiled with a version containing code that, on Windows, mishandles certain path prefixes."

What matters for risk: "Can an attacker trigger this code path in my specific deployment environment?"

For Linux systems, the answer is definitively no. The filepath package includes platform-specific code paths compiled conditionally. On Linux builds, the Windows path handling code simply doesn't execute. The vulnerable functionality isn't just unexploitable, it's literally not present in the compiled binary running on Linux.

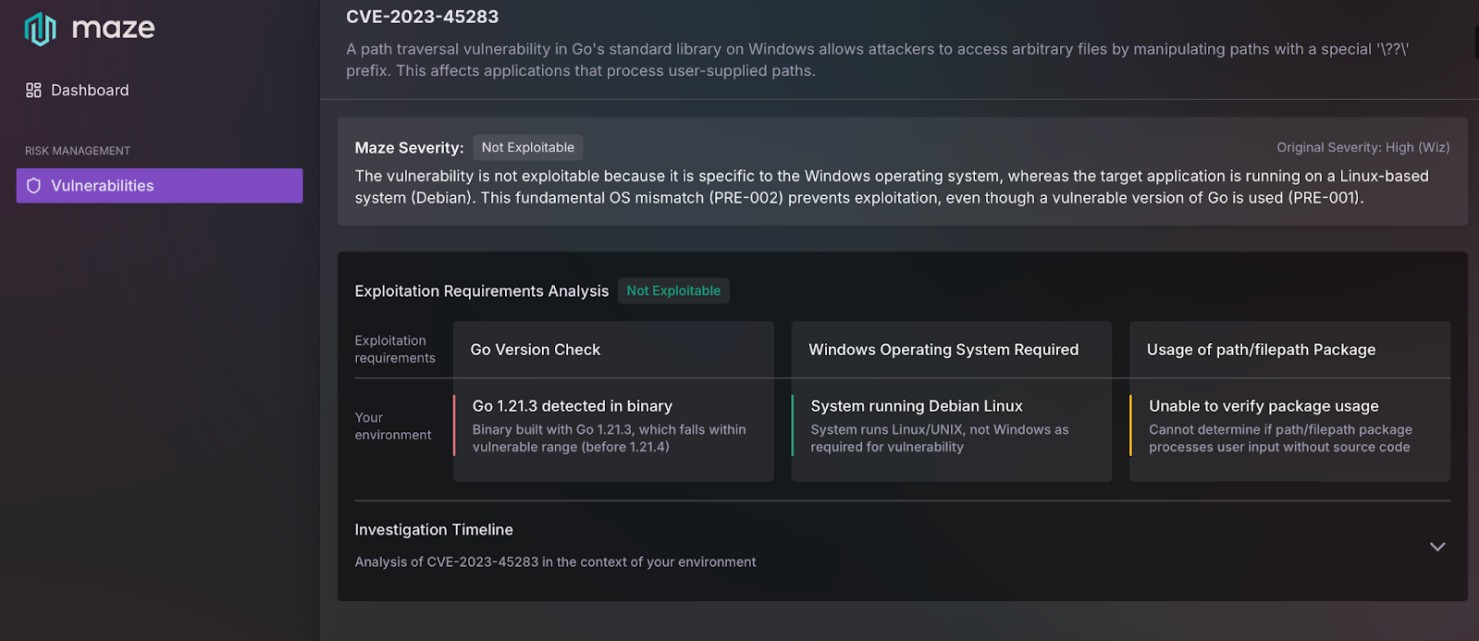

How Maze Solves This Through In-Depth Exploitability Analysis

The workarounds described earlier require manual configuration and ongoing maintenance. Modern platforms use automated analysis to evaluate exploitation requirements systematically. Maze demonstrates this approach through structured requirement analysis that addresses the detection vs. exploitability gap.

Instead of stopping at "vulnerable version detected," the platform breaks down exploitation into specific requirements that must ALL be met. For CVE-2023-45283:

- Vulnerable Go version present (Met)

- Windows operating system (Not Met - blocking condition)

- Application processes user-controlled paths through filepath package (Unknown)

This transforms assessment from binary (present/absent) to conditional (present AND exploitable). Our AI Agents validate the OS context and recognize when it creates a blocking condition, documenting this as prerequisite 002 (PRE-002) not being met. Rather than reporting "CVE-2023-45283 present" and leaving the investigation to security teams, it provides the conclusion: "Not exploitable due to OS mismatch."

This demonstrates how exploitability frameworks eliminate the "dependency fallacy," the assumption that package presence equals exploitability by validating not just what's present but what's actually exploitable. Vulnerability management shifts from high-noise detection to high-signal risk assessment.

Conclusion

Cross-platform false positives, exemplified by cases like CVE-2023-45283 appearing on Linux systems, are symptoms of a larger challenge in vulnerability management: the gap between vulnerability detection and exploitability assessment. While scanners are powerful tools for identifying potential risks, they require context, validation, and intelligent analysis to translate their output into actionable security intelligence.

The workarounds security teams build, such as platform filtering, asset correlation, binary verification, and exception management, represent the operational cost of detection-only scanning. These processes exist to compensate for scanners that can't assess exploitability. Modern platforms that perform this analysis natively eliminate this overhead, making the question clear: continue building workarounds or invest in platforms that solve the problem at the source?

By understanding why cross-platform false positives occur and implementing rigorous validation processes, security teams can reduce noise, improve efficiency, and focus resources on vulnerabilities that pose actual risk to their infrastructure. The goal isn't perfect detection; it's an accurate assessment of exploitability that leads to effective remediation prioritization.